Who was really Muhammad, in Arabic Muḥammad (the praised one), and was the story of the "revelation", which spread around the world from him under the name of Islam, really the story of a misunderstanding, of a fake news?

We will try, in an absolutely non-exhaustive way, to answer these questions, above all because analyzing the issue of the origins of Islam is necessary to understand the historical consequences of the advent of this doctrine.The company is supposedly new in the world.

Let's start with the question of whether it was really a misunderstanding. To do this, we will elaborate three postulates about the credibility of Muhammad and its message:

For us Christians, the first postulate is unacceptable. If it were true, in fact, the foundation of our faith (a faith that, as we have seen, is based on thousands of testimonies and historical documents) would be missing.

On the other hand, the second statement also seems difficult to accept, at least from a scholarly point of view: the hypothesis that Muhammad has been misunderstood is rather strange, mainly because his intention to make himself believe to be a prophet, and not just any prophet, but the last one, the seal of the prophets, is proven.

Therefore, the third hypothesis is the most plausible, so much so that Dante, in the Divine Comedy, places Muhammad, precisely because of his bad faith, in the lower circles of Hell: "Or vedi com'io mi dilacco! Vedi come storpiato è Maometto!" [1] (Hell XXVIII, 30). Others, especially St. John Damascene, identify his message as a Christian heresy destined to die out in a few years.

In any case, it is difficult, if not impossible, to provide a precise and unequivocal answer to the complex questions we have asked. The most widespread opinion among contemporary Islamologists, then, is that Muhammad was really convinced, at least in the first phase of his preaching, in Mecca, in which he plays the role of a heated religious reformer and nothing more, of having received a true divine revelation.

Even more convinced appears later, in the next phase of his public life, called Medinese (to contrast it with the first, known as Meccan), that it was right and necessary to give men a simple religion, in comparison with the monotheisms that existed until then and that he himself had known more or less; a religion stripped of all the elements that did not seem really useful, especially for him.

Everything happened in different phases, in a kind of schizophrenia that caused many doubts regarding the so-called revelation and the bearer of the revelation, even among the most convinced supporters of the self-proclaimed prophet.

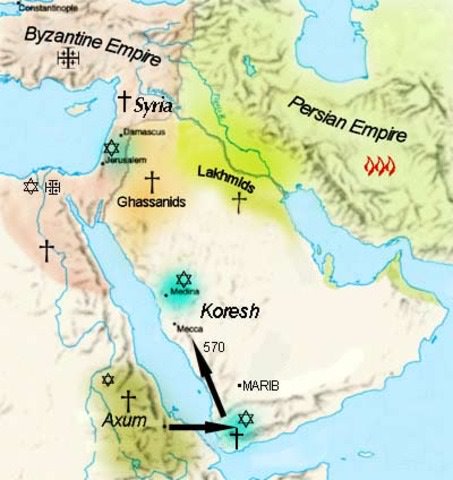

Map Arabia pre-Islam.

The 1975 film "The Message" describes in detail what Mecca was like at the beginning of Muhammad's preaching: a pagan city, immersed in the ǧāhilīya (in Arabic and in Islam, this name, which translated means "ignorance," is attributed to the period before the advent of Islam itself). At that time, in the 6th century CE, Arabia was a frontier area, completely cut off from the so-called civilized world.

It was cut off from the traditional trade routes and the caravan routes (which passed through the "desert ports" such as Palmyra, Damascus or Aleppo to enter Mesopotamia and then, passing the Persian Gulf, reach India and China). However, in periods when the same trade routes were not passable due to wars and political instability, Arabia became a crossroads of great importance. In such cases, there were two routes followed by the caravans: one passed through Mecca, the other through Yaṯrib (Medina).

The cradle of Islam is located right in this area, called Ḥiǧāz, where Mecca (the homeland of Muhammad, born in 570 or 580) and Medina (a city where Muhammad himself took refuge after the disputes arising from his preaching in Mecca: period called hiǧra, in English hegira) are located, main inhabited centers around which orbited nomadic Bedouin tribes, always in struggle with each other.

Herding, hunting, raiding caravans and raids against rival tribes were the main means of subsistence and the harshness of life forged the character of the Bedouins, who had an ideal of virtus, a code of honor: murūwa. This unites the concepts of hospitality and inviolability of the guest, fidelity to the word given, ruthlessness in ta‛r, i.e. revenge for bloodshed and shame suffered.

The religiosity of the nomadic and sedentary people of pre-Islamic Arabia was purely fetishistic: sacred stones were venerated, with vague notions about the survival of the soul after death (completely absurd and mocked was the concept of the resurrection of the flesh, later preached by Muhammad).

Some places were considered holy, in particular the shrine of the Ka‛ba in Mecca, where, during certain proclaimed holy months, people made pilgrimages and held festivals and fairs (in particular poetic contests).

In Mecca, gods such as Ḥubal, Al-Lāt, Al-‛Uzzāt and Al- Manāṯ were worshipped, as well as the Black Stone, set in a wall of the Kaaba, a kind of Arab pantheon in which was also the effigy of Christ (the only one not destroyed by Muhammad at the time of his triumphant return from the hegira in 630).

Before the advent of Islam, Arabia (which had seen the flourishing of a great civilization in the south of the peninsula, that of the Minaeans and Sabeans before and of the Himyarites after, was formally under the rule of the Persians, who had expelled the Abyssinian Christians (a people who had flocked from Ethiopia to defend their co-religionists persecuted by the Sabean kings, of Jewish religion, after the massacre of Christians who were thrown by the thousands into a fiery furnace by King Ḍū Nūwās, in Naǧrān, in 523).

In the north, on the border of the Byzantine Empire, vassal kingdoms of Constantinople had been created, ruled by the Gasanid (sedentarized nomads of Monophysite Christian religion) and Laḥmid (Nestorians) dynasties: these states prevented Bedouin raiders from crossing the borders of the Empire, protecting the most remote regions from it, as well as the caravan trade.

Therefore, the presence of Christian and Jewish elements in the Arabian peninsula at the time of Muhammad is quite certain. These elements, however, were heterodox and heretical, suggesting that the "prophet" of Islam himself was misled about many of the Christian and Jewish doctrines.

There is no precise historical information about the first phase of Muhammad's life (a situation curiously analogous to that of Jesus). About himself, on the other hand, there are many legends that today are part of the Islamic tradition, even though these anecdotes have not been investigated by means of a detailed historical and textual analysis (which did happen, on the contrary, for the apocryphal gospels).

For this reason we find two different historiographies on the self-proclaimed prophet of Islam: one, precisely, Muslim; the other, the one we are going to consider, is the modern Western historiography, which is based on more reliable sources, as well as on the Koran itself, which can be considered, in one way or another, a kind of autobiography of the prophet. Muhammad.

The most certain date we have is 622 (I of the Islamic era), the year of the hiǧra, the hegira, emigration of Muhammad and his followers to Yaṯrib (later renamed Medina).

As for the year of the birth of Muhammad himself, the tradition relates, although not supported by sufficient concrete elements, 570, while several historians agree in giving birth to ours around 580, always in Mecca.

Muhammad was part of the Banū Qurayiš (also called Coraichites) tribe, was born when his father had already passed away and lost his mother at an early age. He was then received first by his grandfather and, after the latter's death, by his paternal uncle Abū Ṭālib.

At the age of about twenty, Muhammad took the service of a wealthy widow who was already of advanced age at the time: Ḫadīǧa, a kind of businesswoman who traded perfumes with Syria. With her (who later became famous as the first Muslim because she was in fact the first person to believe that he was the one sent by God) Muhammad married a few years later.

This union was apparently long, happy and monogamous, so much so that ‛Āʼiša, who, after Ḫadīǧa's death, would later become Muhammad's favorite wife, is said to have been more jealous of the deceased than of all the other wives in the life of the "prophet" of Islam.

With Ḫadīǧa, Muhammad had no children, while from the marriage with Āʼiša were born four daughters, Zaynab, Ruqayya, Fāṭima and Umm Kulṯūm. Muhammad's only son, Ibraḥīm, who died at a very young age, had a Christian Coptic concubine as his mother.

On behalf of Ḫadīǧa, Muḥammad had to travel with caravans to sell goods beyond the Byzantine border, i.e. in Syria. During these travels, he presumably came into contact with members of various heretical Christian sects (Docetists, Monophysites, Nestorians), being indoctrinated by them, without having, as an illiterate, the possibility of direct access to Christian sacred texts. However, we reiterate that elements of the Judaic and Christian faiths - or simply monotheistic ideas, ḥanīf, already existed in and around Mecca.

Everything changed, in Muhammad's life, when he was already around forty years old and abandoned paganism to adopt - and start preaching - monotheistic ideas. Muḥammad was convinced, at least in the early years of his "prophetic" mission, that he was professing the same doctrine of Jews and Christians and that, therefore, even these, as well as pagans, should recognize him as rasūl Allāh, messenger, sent from God.

It was only later, when he was already in Medina, that he himself pointed out the notable differences between his preaching and the official Christian and Jewish doctrine. In fact, the Koran contains distortions of the biblical narratives (both Old Testament and New Testament), as well as Muhammad's docetic ideas in Christology and his confusion regarding the doctrine of the Trinity (in his opinion formed by God, Jesus and Mary).

According to Ibn Iṣḥāq, the first biographer of Muḥammad, when he was asleep in a cave on Mount Ḥīra, outside Mecca, the angel Gabriel appeared to him with a brocade cloth in his hands and telling him to read ("iqrāʼ"); Muhammad, however, was illiterate, so it was the archangel who recited the first five verses of the sūra 96 (called "of the clot"), which, according to him, were literally imprinted on his heart.

This night is called laylat al-qadr, night of power. At first, Muḥammad did not think of himself as the initiator of a new religion, but as the recipient of a revelation transmitted also to other envoys of Allah who had preceded him. He believed, in fact, that what inspired him were passages from a heavenly book, umm al-kitāb (mother of the book), already revealed also to Jews and Christians (called by himself ahl al-kitāb, i.e. people of the book).

Speaking again of the early period in Mecca, it is not difficult to imagine the reaction of the city's notables to Muhammad's preaching, for none of them wanted to subvert the religious status quo of the city, endangering its economic prosperity and ancient traditions, just because of the word of Muhammad, who, although urged, never performed any miracles or gave any tangible sign of the revelations he claimed to have received.

Thus began a persecution of the "prophet" and his followers, to the point that Muhammad had to send at least eighty of them to Abyssinia, to take refuge under the protection of a Christian king.

The Islamic scholar Felix M. Pareja, as well as older Islamic authors, for example Ṭabarī e al-Wāqidī, places in this period the famous episode of the "satanic verses", to which the Qur'an seems to refer in sūra 22/52. [3]

It happened, in fact, that Muhammad, in order to try to come to an agreement with the fellow citizens of Mecca, would have been tempted by Satan while reciting the sūra 53/19 and would have proclaimed:

"How is it that you worship al-Lāt, al-‛Uzzāt and al-Manāṯ Lât, 'Uzza and Manât? They are the exalted Ġarānīq, from whom we await their intercession."

As we have seen, these three goddesses were a fundamental part of the Meccan pantheon and protagonists of various rites that attracted hundreds of pilgrims to the Ka‛ba every year: their title was that of "three sublime cranes" (Ġarānīq) and admitting their existence, in addition to the power of intercession with Allah, if on the one hand it meant reconciling with the Meccan elite and allowing the return of their exiled followers, on the other it meant discrediting himself and the rigid monotheism he had professed until then.

Evidently, the game was not worth playing, so much so that the next morning the "Messenger of God" recanted and declared that Satan had whispered those verses in his left ear, instead of Gabriel in his right; they were to be considered, therefore, of satanic origin. In their place, the following were dictated:

"How is it that you worship al-Lāt, al-‛Uzzāt and al-Manāṯ? [These three idols] They are only names that you and your fathers have invented, and Allah gave you no authority for them."

The episode just cited brought even more discredit to Muhammad, who, with the death of his wife and his uncle-protector Abū Ṭālib, remained without two valid supporters.

Given the situation, he was forced (and the sūra of this period reveal the desolation and abandonment in which he found himself, with the sūra of the ǧinn sūra counting how many goblins became Muslims at those very times) to seek protection elsewhere, something he accomplished by finding valid listeners among the citizens of Yaṯrib, a city north of Mecca, then populated by three Jewish tribes (the Banū Naḍīr, the Banū Qurayẓa and the Banū Qaynuqā‛ and by two Bedouin tribes).

Between the Jews and the Bedouins there was not a good relationship and Muhammad, by virtue of his fame, was called to be an impartial arbiter between the contenders, so that in the year 622, the first year of the Islamic era, began the hiǧra, hegira of the "prophet" and his followers, about one hundred and fifty. The term hiǧra does not mean just "emigration," but estrangement, a kind of renunciation of citizenship and belonging to Mecca and the tribe, with the consequent deprivation of all protection.

Yaṯrib would later be called Medina (Madīnat al-nabī, the city of the prophet). Newly arrived here, in order to win over the Jews, who constituted the wealthy and notables of the city, M. introduced innovations in the primitive Islamic ritual, in particular by orienting the qibla, the direction of prayer, toward Jerusalem. However, when the Jews themselves became aware of Muhammad's confusion in biblical matters, they mocked him, making enemies with him forever.

At that very moment, then, the division began to take place between what would evolve as Islam, on the one hand, and Judaism and Christianity, on the other. Muhammad could not admit that he was confused or that he did not know the biblical episodes he had repeatedly quoted to his followers. What he did, then, was to use his ascendancy over his disciples and accuse Jews and Christians of deliberately falsifying the revelation they received; the same ascendancy and authority are sufficient for Muslims today to continue to believe such accusations.

Once again, however, the intention of Muhammad was not to found a new religion, but to try to restore what, according to him, was the pure and authentic, primitive faith, based on Abraham, who for him was neither a Christian nor a Jew, but a simple monotheist, in Arabic ḥanīf. By that word he was known to the pagan Arabs, who considered themselves his descendants through Ishmael.

And so it was that, in the Qur'an, Ishmael became Abraham's beloved son, instead of Isaac; it is Ishmael whom Abraham is commanded to sacrifice in Jerusalem, where the Dome of the Rock stands today; it is Ishmael who, together with his father, builds the shrine of the Ka‛ba in Mecca, where, moreover, his mother Hagar had taken refuge after being driven out of the desert by Sarah.

Always to take revenge on the Jews, even the direction of the qibla changed, and it was oriented towards Mecca. Islam became the national religion of the Arabs, with a book revealed in Arabic: the reconquest of the holy city thus became a fundamental purpose.

In Medina, in the figure and in the person of Muhammad, religious and political authority meet, and it is there that the concepts of umma (the community of Muslim believers), of Islamic state and of ǧihād, holy war, are born: the community of Medina, with the various religions. That were professed there (Muslim, Jewish, pagan), lived in peace under the rule of the arbiter, and already political and religious authority, who came from Mecca.

The Muslims prospered particularly well, guaranteeing themselves considerable income through raids on passing caravans. Successes and failures (successes were called divine work, failures lack of faith, indiscipline and cowardice) alternated in the campaigns against the Meccans.

In a few years, however, Muhammad decided to get rid of the Jewish tribes that had become hostile in the meantime: the first were the banū Naḍīr, followed by the banū Qaynuqā‛, whose property was confiscated but whose lives were spared; a more atrocious fate, on the other hand, befell the banū Qurayẓa, whose women and children were enslaved, and whose men, once their property was confiscated, had their throats slit in the square (there were about seven hundred dead: only one of them was spared as he converted to Islam).

In the sixth year of the Hegira Muhammad In the sixth year of the Hegira M. claimed to have received a vision in which he was given the keys of Mecca. He then began a long campaign of reconquest, violating a truce (something that was terribly dishonorable for the time) and taking, one after another, the rich Jewish oases north of Medina. The economic and military success was a magnet for the Bedouins, who began to convert en masse (obviously not for religious reasons). It all culminated in the triumphal entry into the city of origin in 630, without encountering resistance. The idols present in the Ka‛ba (except the effigy of Christ) were destroyed.

The following two years saw the consolidation of the strength and power of M. and his followers, until, in 632, the "prophet" died, in the midst of fever and delirium, without indicating successors.

What emerges from an analysis of Muḥammad's life is above all his great ambiguity, along with his personality that scholars often define schizophrenic, because of how contradictory his attitudes and speeches are, as well as the very revelations reported in the Qur'an. It is for this reason that Muslim scholars and theologians will resort to the practice of nasḫ wa mansūḫ (abrogating and abrogating, a procedure according to which, if one passage in the Qur'an contradicts another, the second nullifies the first). [4]

It may serve as an example of this the episode in which M. goes to the house of his adopted son Zayd (this same episode is quoted in the conclusion of this article) and many others: extravagant and suspicious circumstances in which Allah literally comes to Muhammad's aid and reveals to him verses admonishing the unbelievers and the doubtful who dare to accuse him of having entered into contradiction; or also words encouraging Muhammad himself not to want to follow the laws and customs of men and to accept the favors that God bestowed only on him:

"Sometimes they have wanted to see themselves in Muhammad two almost contradictory personalities; that of the pious agitator of Mecca and that of the overbearing politician of Medina. [---] In his various aspects he seems to us generous and cruel, timid and bold, warrior and politician.

His way of acting was extremely realistic: he had no problem in abrogating one revelation by replacing it with another, in going back on his word, in making use of hired assassins, in letting the responsibility for certain actions fall on other people, in making up his mind between hostilities and rivalries. His was a policy of compromises and contradictions always aimed at achieving his goal. [Monogamous until his first wife lived, he became a great friend of women as circumstances permitted and showed a predilection for widows". [5]

Gerardo Ferrara

BA in History and Political Science, specializing in the Middle East.

Responsible for students at the University of the Holy Cross in Rome.