Analyzing the issue of the origins of Islam is necessary to understand the historical consequences of the advent of this doctrine.

Here you can read the first installment of this analysis.

The term "Koran" is derived from the Semitic root qaraʼa, in the sense of recitation or recited reading, hence psalmody. Already in antiquity, Christians and Near Eastern Jews used the equivalent Aramaic voice, qeryan, to indicate the solemn recitation of sacred texts. However, the use of the same root is even older: ʼAnī qōl qōreʼ ba-midbar (Hebrew: voice of one crying out in the wilderness, as in the book of the prophet Isaiah, later quoted in Greek in the New Testament) has the meaning to cry out, to call, to proclaim, to sing.

The Koran is the sacred text of Muslims. For most of them it is the uncreated word of God. It is divided into one hundred and fourteen chapters, called sūra, with their respective verses, called ayāt. For any non-Islamic exegete, there are many passages in the text that are identical or parallel to those in other older documents, the Old and New Testaments in the first place, as well as pre-Islamic practices, traditions and customs such as belief in goblins, ǧinn, pilgrimage rites, legends of vanished peoples and the veneration of the Ka‛ba.

The problem of Qur'anic sources is therefore very important. Such sources can certainly not be something written, since Muhammad, universally considered the author (by scholars) or bearer (by Muslim believers) of the revelation reported in the Qur'an, was illiterate and could not, of course, have personal access to the reading of Christian and Jewish holy books. Consequently, it is in oral form that many religious notions of Christianity and Judaism reached their ears, and this in two phases: the popular festivals that were held periodically in Mecca, where proselytes of heretical Christian and Jewish sects often took refuge to escape persecution in the Byzantine Empire (that can be deduced from many heretical Christian notions and reminiscences of the haggadah books and apocryphal books of which the Koran abounds) and, as we said, the commercial journeys that M. made beyond the desert (again the notions he had to learn are few, imprecise and incomplete, as is evident from the Qur'anic quotations).

We have seen, then, that Muḥammad was immediately convinced that he was the subject of a revelation already communicated to other peoples before him, the Jews and the Christians, and that it came from the same source, a heavenly book which he called umm al-kitāb. However, the communications in his case occurred intermittently, which caused opponents to laugh at him. We have also seen that Allah often provided the latter with incredibly appropriate responses to his demands and difficulties and admonitions, such as the following:

"The disbelievers say: 'Why has not the Qur'an been revealed to you all at once? But [know, O Muhammad, that] We have revealed it to you gradually, that We may thus strengthen your heart. And whenever they present an argument [against the Message] We will reveal to you the Truth, so that you may refute them with a clearer and more evident foundation.[1]".

The result of such intermittency, and of Muhammad's habit of often changing his version, is the fragmentary character of the Qur'an, as well as the lack of a logical and chronological order: everything is for immediate use and consumption. This was already obvious to the early Qur'anic commentators, shortly after the death of the "prophet" of Islam, particularly with regard to the question of verses abrogated by later ones. To try to resolve the matter in the best way, the sūra were classified into Meccan and Medinan, according to the period in which they were revealed.

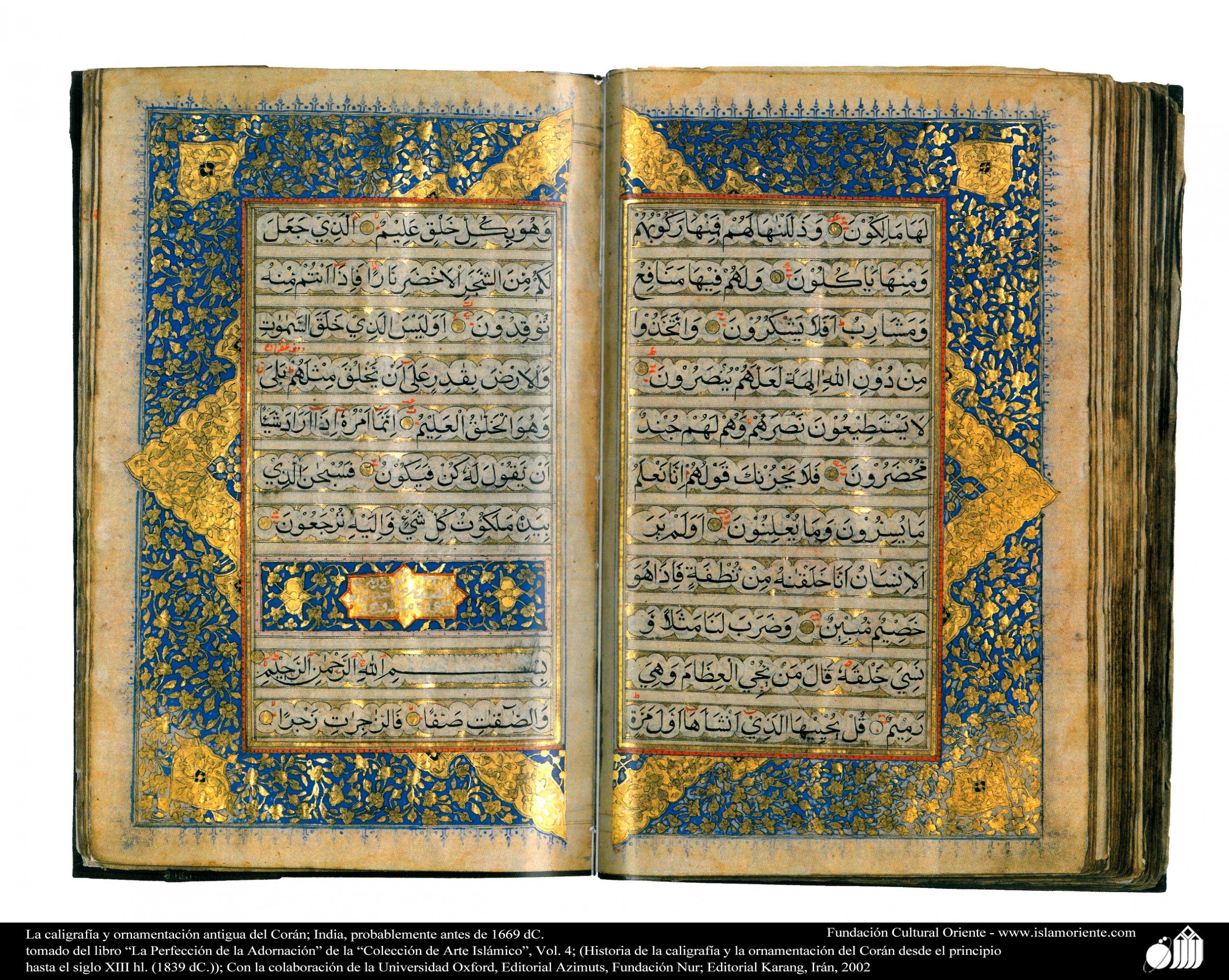

The ancient calligraphy and ornamentation of the Indian Qur'an probably predated 1669 AD.

It is divided into three phases: a first, corresponding to the first four years of Muhammad's public life, characterized by brief, passionate and solemn sūra, with short verses and teachings full of force intended to prepare the minds of the listeners for the day of judgment (yawm al-dīn); a second, covering the next two years, in which the enthusiasm, at the beginning of the persecutions, cools down and stories are told about the lives of the previous prophets, in a form very similar to the haggadah (rabbinic literature of a narrative and homiletic type); a third, from the seventh to the tenth year of public life in Mecca, also full of prophetic legends, as well as descriptions of divine punishments.

We find the great change undergone by M. after the hegira. The sūra are addressed to Jews and Christians, and the friendly and laudatory tone reserved for them in the first phase is gradually lost, culminating, in the last years of the life of the "prophet" of Islam, in a real attack. It is of this age, for example, the sūra 9, in which, in verse 29, it is demanded: the humiliation of:

"Fight those who believe neither in Allah nor in the Day of Judgment, do not respect what Allah and His Messenger have forbidden, and do not follow the true religion [Islam] from among the People of the Book [Jews and Christians], unless these agree to pay a tax [whereby they are allowed to live under the protection of the Islamic state while retaining their religion] with submission."

This will be translated into laws that will impose various restrictions on those who profess the Jewish or Christian religion, such as dressing in a special way, not being able to carry weapons and ride horses, etc.

Although the Pentateuch, the Psalms and the Gospel are explicitly admitted as revealed by the Koran, there are considerable differences between Islam and Judaism, and even more between Islam and Christianity. These divergences, as we said, reflect the contacts between Muhammad and the heretical Christian sects, whose existence at that time was quite common both in the Byzantine Empire and, above all, just outside its borders. Among the most obvious divergences are those related to the figure of Christ, whereby the Christian apocryphal books exert a particular influence on the Koran. In the holy book of Islam, for example: Jesus is the son of Mary and was born of a virgin birth, and yet this Mary is the sister of Moses; the miracles performed by Jesus from infancy are narrated in great detail, and he is attributed the names of Messiah, Spirit of Allah and Word, placing him on a level of superiority with respect to the other prophets, but it is specified that Christ is only a servant of Allah, a man like the others; it is established, among other things, that his death on the cross would never have occurred: instead of Jesus, only a simulacrum would have been crucified.[2].

Another considerable difference, which for Islam is something absolutely earthly (another reason why we speak of Islam as a natural religion), made to impress the simple and rough inhabitants of the desert: green gardens, enchanting streams, wine that does not intoxicate, virgins always untouched. There is nothing there to express the concept of the beatific vision and the participation of believers in the very life of God: Allah is inaccessible to human vision (6/103).

Finally, among other differences, there is the predetermination of human actions by Allah (in this respect Islam is very similar to Calvinism). There are passages of the Koran more or less in favor of or completely opposed to free will, but it is the latter that have been accepted, with skillful corrections, by Sunni orthodoxy, and that to give Islam its predeterminist mark (the maktub, the destiny of each man, is rigidly written and predetermined by God).

The actual compilation of the Qur'an is subsequent to Muhammad's death, at which time the compilation of all the fragments of the revelation that he himself had entrusted to his followers began. The sūra were ordered by length (from the longest to the shortest, although with several exceptions, also due to the impossibility of a logical or chronological order). To this same period goes back the beginning of the fierce struggles and internal divisions, between various parties and currents, struggles all suffocated in blood, with each side fabricating verses and Koranic quotations à la carte that supported the respective claims.

Put a face to your donation. Help us form diocesan and religious priests.

It is an Arabic word meaning "beaten path", like halakhah in Hebrew, and indicates the written law From a semantic point of view, both terms, Arabic and Hebrew, can be assimilated to our "law" ("direct" path, way to follow). The Šarī‛a, Islamic law or law (according to the "orthodox" Sunni view), is based on four main sources:

As we have already spoken of the Koran, let us analyze directly the other three sources, starting with the sunna (habit, tradition, line of conduct of the ancestors), which is a word that indicates, even before Muhammad, the traditional customs that regulated the life of the Arabs. In the Islamic context, the same term defines the set of sayings, deeds and attitudes of Muhammad according to the testimony of his contemporaries. And it is here that the ḥadiṯ comes into play, i.e., the narration or account of Muhammad's sunna made according to a given scheme, based on isnād (support and enumeration in ascending order of the persons who reported the anecdote until reaching the direct witness of the episode) and matn (the text, body of the narration). This source was extremely necessary when, at the death of M., Islam was only a draft of what would later become. It was also necessary, after the conquest of such vast territories and the consequent confrontation with new cultures, to find solutions to problems and difficulties with which the "messenger of God" had never been directly confronted.

And it was precisely Muhammad who was called upon so that he himself could specify, although he had already passed away, a number of points that are only hinted at in the Qur'an or were never addressed, in relation to various disciplines. Thus, a set of true, presumed or false traditions was created at a time when each of the factions fighting within Islam claimed to have M. on their side and attributed this or that claim to him, constructing entire apparatuses of totally untrustworthy testimonies. The method adopted to stop this overflowing flow was extremely arbitrary. In fact, neither textual analysis nor the internal evidence of the texts was used (the same can be said with regard to Koranic exegesis which is almost non-existent), which is the criterion par excellence, in Christianity, to determine and verify the authenticity of a text. On the contrary, reliance was placed exclusively on the reputation of the guarantors: if, therefore, the chain of witnesses was satisfactory, anything could be accepted as true. It should be noted, in this connection, that the traditions defined as the oldest and closest to Muhammad are the least reliable and the most artificially constructed (something that can also be ascertained by the excessive affectation of the language).

The third source of Islamic law, or Šarī‛a, is the qiyās, or deduction by analogy, through which, from the examination of determined and resolved questions, the solution was found for others not foreseen. The criterion used, in this case, is ra'y, i.e. point of view, intellectual view, judgment or personal opinion. The source in question became necessary from the dawn of Islam, since, as we have seen, the inconsistency of the Qur'an and the ḥadīṯ had produced considerable confusion and led to the entry into force, for the first two sources, of the tradition of the abrogator and the abrogated.

However, if in case the qiyās had not been sufficient to resolve all unresolved issues, a fourth source, the vox populi or iǧmā‛ (popular consensus) was inserted to provide a solid basis for the entire legal and doctrinal apparatus. This source seemed more than justified for both Qur'anic quotations and for some hadīṯ, in one of which Muhammad claimed that his community would never err. The iǧmā‛ may consist in a doctrinal consensus reached by the doctors of the law; in a consensus of execution, when it concerns customs established in common practice; in a tacit consent, even if not unanimous, by the jurisconsults, in the case of public acts not involving the condemnation of anyone.

The constructive work to derive the law from the four sources indicated (Qur'an, sunna, qiyās and iǧmā‛) is called iǧtihād (da ǧ-h-d, the same root as the term ǧihād), or "intellectual effort." The effort in question, a true elaboration of Islamic positive law, based however on a "revealed" word, lasted until around the tenth century, when the legal schools (maḍhab) were formed, after which "the iǧtihād gates" are considered officially closed. From then on, one can only accept what has already been settled, without introducing further innovations (bid‛a). The most rigid in this respect are the Wahhabis (founded by Muḥammad ibn ‛Abd-el-Waḥḥḥab: the Wahhabi doctrine is the official doctrine of the kingdom of the Sa‛ūd, absolute monarchs of Saudi Arabia) and the Salafists (founders and main exponents: Ǧamal al-Dīn al-Afġāni and Muḥammad ‛Abduh, 19th century; the Muslim Brothers are part of this current). According to the view of both movements, within Islamic doctrine excessive innovations were introduced; therefore, it is necessary to return to the origins, to the golden age, that of the fathers (salaf), in particular that of Muhammad's life in Medina and of his first successors, or caliphs.

Before proceeding further, we may say a few words regarding the concept of ǧihād. Muslim law considers the world divided into two categories: dār al-islām (house of Islam) and dār al-ḥarb (house of war): against the latter, Muslims are in a state of constant war, until the whole world is not subject to Islam. The ǧihād is so important, in Islamic law, that it is almost considered a sixth pillar of Islam. In this sense, there are two obligations to fight: a collective one (farḍ al-kifāya), when there is a sufficient number of troops; an individual one (farḍ al-‛ayn), in case of danger and defense of the Muslim community.

There are two types of ǧihād, one small and the other large. The first is the duty to fight to propagate Islam; the second is the daily and constant individual effort in the way of God, in practice, a path of conversion. It is through the ǧihād that many Christian lands have fallen, most often by capitulation, into Islamic hands and, in this case, their inhabitants, considered "people of the covenant" or ahl al-ḏimma, or simply ḏimmī, have become state-protected subjects, second-class citizens subject to the payment of a capitulation tax, called ǧizya, and of a tribute on lands owned, ḫarāǧ.

Gerardo Ferrara

BA in History and Political Science, specializing in the Middle East.

Responsible for the student body

University of the Holy Cross in Rome