On January 28, 1972, 50 years ago, Dino Buzzati died at the La Madonnina clinic in Milan. A name of reference in Italian journalism, linked to Corriere della Sera.

A multifaceted man, cultivator of art, music and Italian literatureDino Buzzati will always be remembered for his novel The desert of the Tartars. A story of high symbolic value, an example of the so called waiting literaturewith parallels to Kafka's The Castle and Beckett's Waiting for Godot.

Its protagonist is the officer Giovanni Drogo, custodian of a fortress over which lurks a threat, that of the Tartars, obsessively present but never materializes in time. The result is anguish, sadness and resignation, with which life is paralyzed by an event that has never happened, and that, if it did, would catch those who await without the vital tone to react.

This is the chronicle of a hopeless wait, in which security is more valuable than freedom, because freedom implies risk, although fear avoids assuming it. Life becomes a frustration, an inner desert without expectations. As Borges wrote, the hero of the story expects crowds, although the reality is that the desert is empty. It could be added that is the novel of procrastination, one of the greatest dangers of human existence.It implies a renunciation of daily life and of doing what needs to be done at any given moment.

Dino Buzzati did not share the method of procrastination. He was a man with a great sense of duty, of quiet and passionate work, although at the same time he was very emotional, for as a child his readings had led him along the paths of fantasy and imagination. He received a Christian education, but the flame of faith had gradually died out.

The poet Eugenio Montale wrote, however, an obituary article in which he affirmed that Buzzati was a naturaliter christiano. He claimed not to believe, but his life is full of references to a search for God.. He even wrote a poem in which he prays to a God in whom he does not believe, whom he calls, but, in spite of everything, "by the terrible strength of my soul, he will come". However, the problem of God, according to the writer, is the belief in the afterlife.

Whoever does not believe in the hereafter, cannot believe in God. Dino Buzzati insisted that he was not a believer, but as a good journalist, he asked incisive questions to those who believed. This was the case of Sister Beniamina, a nun who attended him in the last month of his life in the Milanese clinic where he had been admitted for pancreatic cancer.

He also had a book on his bedside table, Pascal's Pensées, because he identified himself with the search for the hidden God of which the French philosopher spoke. Like Pascal, Buzzati rejected Cartesian rationalism, of blind faith in reason and intellect, which leads, whether one wants it or not, to put God in parentheses.

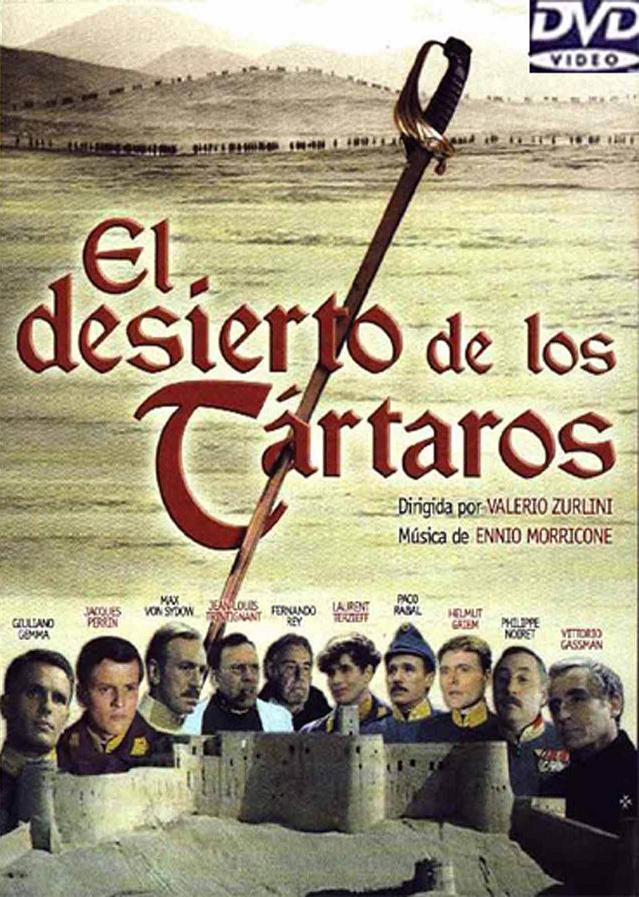

Dino Buzzati's novel was adapted to film in 1976 by Valerio Zurlini.

Whoever seeks God is someone who realizes the fragility of mankindthe "thinking reed" referred to by Pascal. This search reflects the need for a creator. In a confidence to a journalist friend, Buzzati pointed out that, without his creator, "man is an atom lost in the desert maelstroms of the universe".

He also said that "the desire for God in man has weakened and a dreadful emptiness has arisen, which is the tragedy of the modern world". In spite of everything, in the clinic the writer did not want to call a priestDid he consider it an easy solution to release the weight of the faults of his life? Surely, Dino Buzzatti had not taken on board the words of the prophet Isaiah, often quoted by Pascal, those that say that "though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow." (Is 1:18).

However, Dino Buzzati kissed in her last moments the crucifix that Sister Beniamina wore around her neck.That same day, when an unusual snowfall fell on Milan, he asked his wife to shave him, as he wanted to be presentable for the most important meeting of his life.

A good friend of Buzzati, the priest David Maria Turoldo, wrote a poem in which he refers to an atheist brother who goes in search of a God that he does not know how to give him, but offers to cross the desert together. It is worth remembering that the desert has the quality that the footprints are often marked in the sand.

In a confidential letter of August 1971 addressed to Gioacchino Muccin, bishop of Belluno, Buzzati's hometown, the writer pointed out that he had knocked on God's door and the door had opened, although he also added that this was not to be counted for ten years.

Some critics of Dino Buzzati's works insist that it is useless to look for an alleged Christianity in them. They see spiritualism, but not spirituality or transcendence. On the other hand, I'm left with the agonizing Buzzati who kisses the Crucified. In those moments one only kisses what one really loves.

With the collaboration of:

Antonio R. Rubio Plo

Degree in History and Law

International writer and analyst

@blogculturayfe / @arubioplo